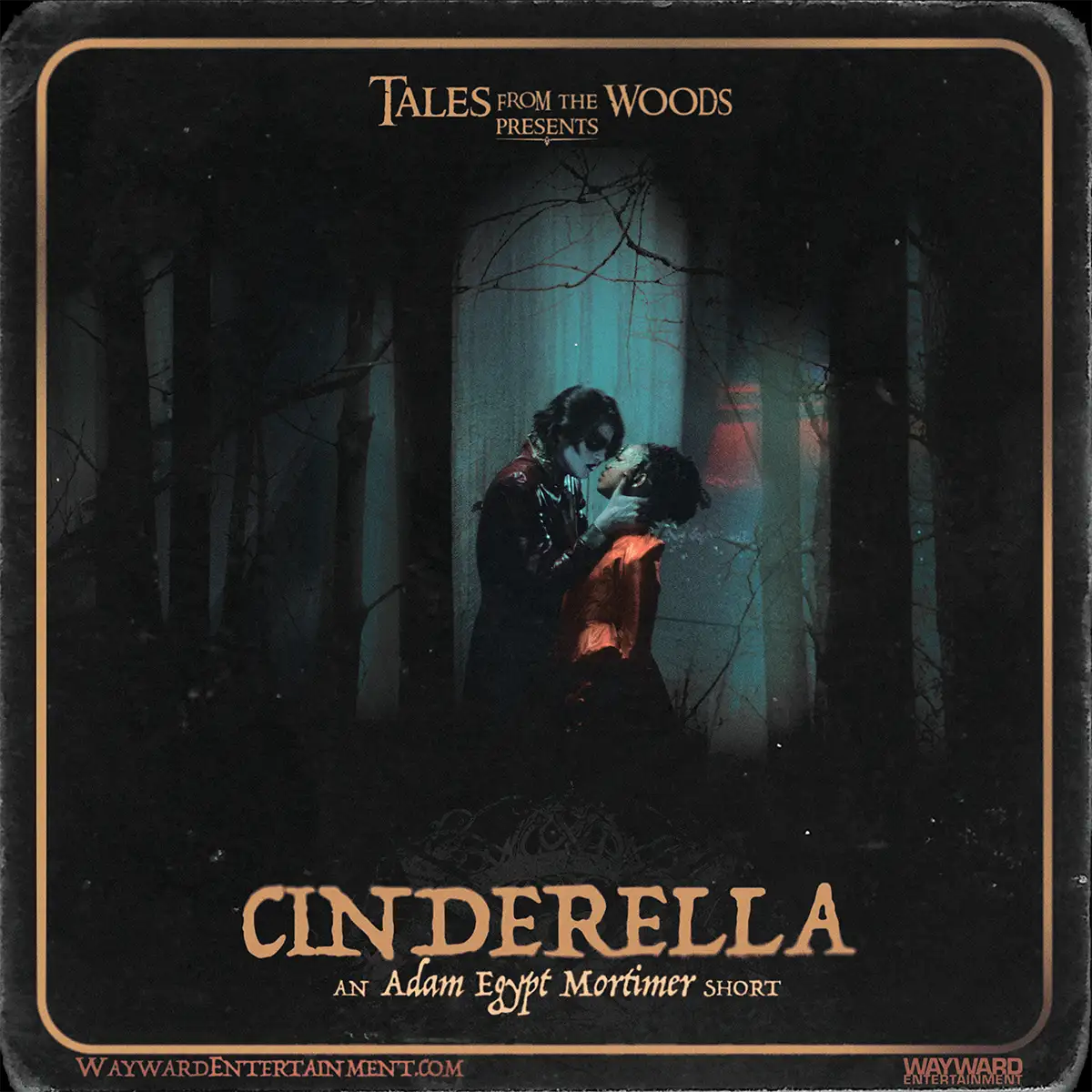

Cinderella reaches deep into the violent roots of the story to expose The Prince as the true villain, a sadistic ruler manipulating people into competing with each other to chase their royal dreams –until Cinderella arrives with her animal magic to take revenge.

A planet ravaged by toxins. A kingdom ruled by fear. Cinderella makes a pact with the haunted woods to meet the Prince and to bring retribution to his fortress.

A NOTE FROM THE DIRECTOR

When I read Charles Perrault’s version of Cinderella, written in 1697, two things fascinated me. The first was the evil and the brutality — The stepsisters cutting off their own toes to fit the slipper, the prince stalking Cinderella back to her home and destroying her father’s property to find her. The second was the style: the story is written in a flowery, decorative French — unlike Hans Christian Anderson’s later approach of writing Fairy Tales for the people, Perrault was writing in a way deliberately crafted to delight the educated, the aristocracy, the ruling structure. Perrault was a kind of courtesan fool, an entertainer turning his back on the lower class, sucky up to powdered wigs who would in the next century have their heads removed from their bodies. No wonder every supposedly happy ending depicted a poor girl marrying the prince — these were stories crafted to entertain the prince. What better entertainment than to be told that you and you alone were the only happy ending for a beautiful and pure young woman of the kingdom?

And so I realized that the prince is the bad guy of the story, the architect of a power structure that reduces resources in order to force a brutal competition among the population. If the stepsisters hate Cinderella, it’s because when she joins their family, that merger reduces all of their resources: it cuts into their dowry and threatens them with endless poverty. I imagined Cinderella as a figure of vengeance — one who can see through the cheap tricks used by the power structure to create conflict and chaos among those who should be uniting against it. I imagined her as a young witch, connecting, through the spirit of her mother, to the dark roots of the earth and the magic underneath the woods.

In contrast is the prince, a figure of living death, of unrelenting, bleak power. I imagined the prince as an inheritor — he’s not the one who fought and killed to take his land and ownership. That was his father, or his father’s father — he is himself nothing more than a mouth, an unproductive spirit who nonetheless can command the death of the people with a lazy gesture.

In searching for the right setting, I wanted something timeless and folk, but I didn't want to see the same horses and castles of Charles's Perrault's fairy tale fantasy. I imagined a world in the

future, utterly devastated, a neon medieval landscape that suggests the aftermath of social collapse. Maybe The Prince's grandfather built a bunker to survive, and now this is the world left to his descendants.

The conflict between the earth magic of Cinderella and the neon brutalist concrete of the Prince set the stage for a story of goth romantic revenge. Shooting two thirds of the project on a LED volume stage allowed me and my crew to create a fully immersive world that feels both inevitably futuristic and a little bit classic, so that Cinderella could be less a princess and more a sci-fi samurai witch.